Is America a racist place? Like, fundamentally and deeply racist? When historians look around, they tend to say yes. But as a terrific new book about the 1920s Ku Klux Klan makes clear, saying that white racism has always been a central part of American culture is only the beginning. If we really want to understand white racism in America, we need to be prepared to wrestle with some complicated and uncomfortable facts.

We can see the dilemma everywhere we look these days. White nationalism seems to be thriving, as we saw in the 2016 presidential elections. We also see it all over today’s college campuses. And—as I argued recently in Religion Dispatches—we find it in places we might not expect, such as evangelical colleges and universities.

But white nationalism is only part of the story. These days, every triumph of Trumpishness is also a catalyst for anti-Trump activism.

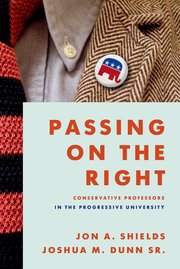

This paradox at the heart of American identity is made disturbingly clear in a wonderful new book by Felix Harcourt. Harcourt examines the impact of the 1920s Ku Klux Klan on the wider American culture of the 1920s. I’ve spent my share of time studying the 1920s Klan—it was a big part of my book about the history of educational conservatism.

Harcourt’s book raises new and intriguing ways to understand the everyday bigotry associated with the Klan of the 1920s. When most of us imagine the Ku Klux Klan, we think of the much smaller, much different Civil-Rights-era group. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Klan had been reduced to small clusters of southern hillbillies lashing together dynamite bombs and informing for the FBI.

The 1920s Klan wasn’t like that. Some of the symbols were the same, such as the fiery cross, the infamous hood, and the night-rider imagery. In the 1920s, though, membership in the Klan boomed into the millions. Instead of hunkering down in barns and basements, the 1920s Klan seized Main Street with lavish parades and open celebrations of “100% Americanism.” The organizations briefly ran the government of states such as Indiana and Oregon. Its main bugbear was not voting rights for African Americans, but rather infiltration by Catholics and other sorts of immigrants.

Not that the 1920s Klan wasn’t fiercely controversial. It was. Even as it attracted endless criticism, however, it also attracted millions of members, each coughing up ten dollars for required accoutrements and registration forms.

Professor Harcourt does the best job any historian has done yet of capturing this American paradox. He examines the way the Klan presented itself in newspapers, books, and other media. He also looks at the ways outsiders unwittingly helped drive membership by attacking the Klan. As Harcourt makes abundantly clear, the real lesson of the 1920s Klan lies in its everyday radicalism, in the way its members thought of the Klan as a muscle-bound Rotary Club, another expression of their Main-Street claim to white Protestant supremacy.

For example, journalists in Columbus, Georgia took great personal and professional risks to confront their local Klan. They went undercover to expose their governor as a Klan stooge. The upshot? Their newspaper won a Pulitzer Prize for brave investigative journalism but the outed governor won a landslide re-election.

Beyond electoral politics, the 1920s Klan made a huge impact on popular culture. As Harcourt recounts, publishers generally were more interested in exploiting the Klan’s controversial reputation than in supporting or denouncing it. Maybe the best example of this was the June, 1923 special edition of the pulp magazine Black Mask.

“Rip-snorting” racism.

In a masterpiece of blather, the editor told readers of the Klan issue that the hooded empire was

the most picturesque element that has appeared in American life since the war, regardless of whether or not we condemn its aims—whatever they may be—or not.

This same editor told one author to provide a “rip-snorting dramatic tale” about the Klan, but to leave out any sort of controversy. In the story, “Call Out the Klan,” a WWI veteran investigates the Virginia Klan who has kidnaped his love interest. Turns out it was fake news—a non-Klansman put on robes and hood and kidnaped the southern belle in order to discredit the Klan. In the end, the true Klan saved the day, in particularly dramatic fashion. The story includes no mention of racism, anti-Semitism, or anti-Catholicism.

The 1920s Klan was at once frightening and fascinating; lauded as a tough answer for tough times and excoriated for anti-democratic thuggery; hailed as America’s salvation and cursed as its damnation.

In our popular memory, the Klan is usually conveniently dismissed as a nutty group of thugs and crazies. In fact, as Harcourt reminds us, “the men and women of the Klan were far from aberrant and far from marginal.”

Those of us who were shocked by President Trump’s surprise electoral victory in 2016 should heed these historical lessons. White nationalism has always been able to mobilize Americans. Many of us get off the couch to fight against it, but equally large numbers will fight in favor.

And though no one says President Trump is a latter-day Clifford Walker, it’s difficult not to get spooked by some of the parallels. As one Klansman told reporters, the Klan’s strategy was always to attract attention, no matter what. As he put it, “the Klan organization dealt very deliberately in provocative statements, knowing they would garner front-page headlines.”