I wasn’t. Studying populist conservatism taught me the wrong lessons—I thought conservatives would never tolerate an anti-strategic leader like Trump, even if they liked his policies. I wrongly believed more conservatives would do anything to maintain their reputations as respectable mainstream traditionalists. Did anything in your background prepare you to have a president who flits from tweet to tweet and treats foreign policy like a reality-TV ratings sweep?

Peter Greene says his did. As he wrote recently,

In many ways, becoming a student of ed reform prepared me for a Trump presidency, because it made me really confront the degree to which many of my fellow citizens do not share values that I had somehow assumed were fundamental to being a citizen of this country.

Here’s where I went wrong: In my 2015 book The Other School Reformers, I looked at the kind of populist conservatism to which Trump appeals so strongly. I didn’t study conservative intellectuals, but grass-roots activists who tried to push schools in conservative directions.

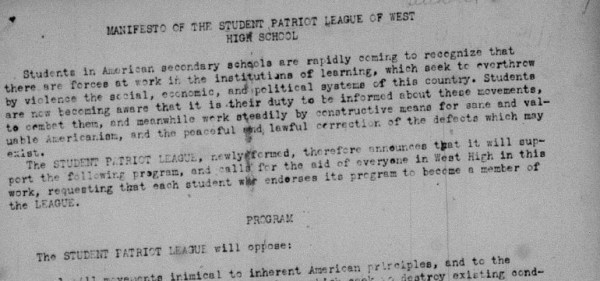

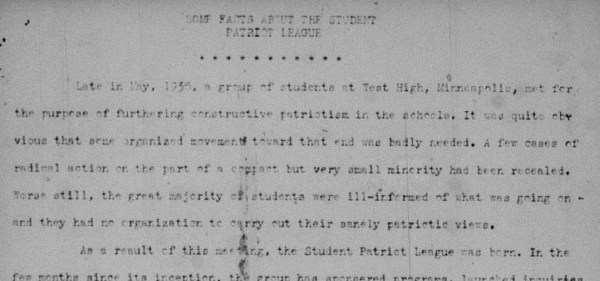

From the American Legion Archives, c. 1936.

Throughout the twentieth century, conservatives refused to be dominated by the anti-strategists in their camp. Time after time, conservative organizations carefully curated their public image to avoid the “extremist” label. Not all of them, of course, but the ones that really mattered. I thought—wrongly—that this pattern would continue.

My surprise is not about Trump’s specific policies. I can see how any conservative would love having Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh on SCOTUS. My surprise is about style and strategy. In the history of American grass-roots conservatism there has always been an element we might call “Trumpish.” Meaning mercurial, impulsive, and unwilling to think through the likely consequences of any given action. Meaning acting first—speaking without reflection—heedless of accusations of radicalism or extremism. In Krusty-the-Klown terms, Trumpism means saying the quiet part loud and the loud part quiet.

In the past, that element was always held in check. Not by “faculty lounge” conservatives, but by practical, hard-nosed activists who wanted to win votes long-term.

This morning I’ll share an example from the archives that I hope will illustrate the tradition and demonstrate why I was so un-prepared for the triumph of Trumpism among American conservatives.

Exhibit A: The American Legion and the Student Patriot League, c. 1935. In the mid-1930s, the American Legion had a hard-earned reputation as a tough defender of a conservative patriotism and flag-waving militarism. The Student Patriot League was formed separately as part of a desire to get young people involved in fighting—literally fighting—for those values. The unofficial goal of the SPL was to send uniformed brigades of conservative youth to leftist rallies to disrupt them.

How did the American Legion respond? At the time, the obstreperous head of the Americanism Commission, Homer Chaillaux, engaged in a careful two-sided interaction. Officially, the American Legion had no relationship with the SPL. Chaillaux was worried that any violence would ruin the Legion’s already-shaky reputation as a reputable mainstream group. Publicly, Chaillaux maintained a careful distance between the SPL and the Legion. He told SPL leaders that he could not officially endorse their activities.

Unofficially, however, Chaillaux distributed SPL materials among his friends and allies. Chaillaux privately told his friends the SPL was a

splendid organization of scrappy young Americans who are students in high schools and colleges of the United States.

So what? The interactions between the Legion and the SPL demonstrate the ways grassroots conservative organizing used to work. There is no doubting Chaillaux’s dedication to his conservative principles. When it came to a new and untested youth organization, however, Chaillaux maintained a cautious official distance.

Conservatives used to care about their reputations for mainstream respectability.

That has always been the strategy of (most) conservative organizations. They have thought carefully and deliberately about their public image. They have been leery of losing credibility and ending up dismissed as extremists, like the Ku Klux Klan or eventually the Birchers. Or even Barry Goldwater or Curtis LeMay. Mainstream respectability used to matter to conservatives. A lot.

Trump doesn’t seem to care about his respectability. He doesn’t seem to mind the outrage and consternation caused by his last-minute decisions, even when the outrage comes from his own conservative allies. Instead, Trump does Trump and lets the chips fall where they may. That’s what I was unprepared for.

How about you? Were you like Peter Greene, prepared for the triumph of Trumpism? Or were you more like me, expecting GOP leaders to care primarily for their public image as respectable maintainers of the mainstream status quo?

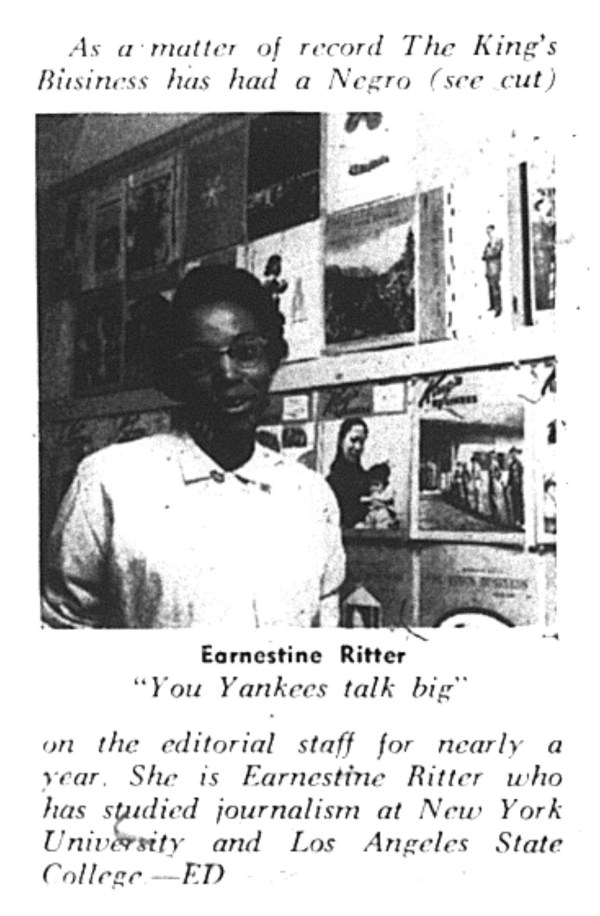

Hamill did not back down. He pointed out that the offices of King’s Business did not only advocate racial integration, they practiced it. As Hamill noted in the following issue,

Hamill did not back down. He pointed out that the offices of King’s Business did not only advocate racial integration, they practiced it. As Hamill noted in the following issue,

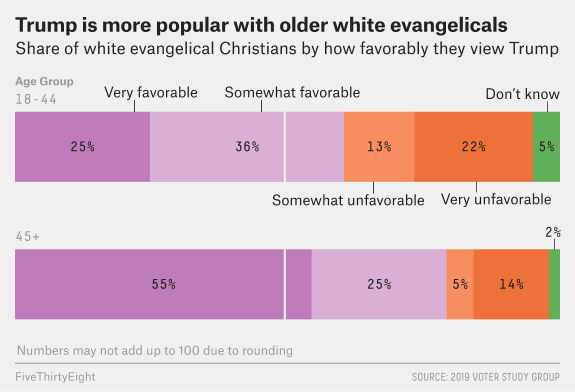

Tough times for evangelical colleges, at WORLD

Tough times for evangelical colleges, at WORLD