SAGLRROILYBYGTH have heard it all before. For the past century, conservative evangelicals have warned that their religious beliefs have made them the target of anti-Christian religious discrimination and persecution. Today we hear the same warning from radical young-earth creationist Ken Ham. So should Christians be afraid?

First, the history: In spite of today’s rosy nostalgia, evangelical Protestants have always felt themselves the targets of creeping secular attack. To pick just one example, when SCOTUS ruled against devotional Bible-reading in public schools in 1963, evangelicals responded with apocalyptic alarm.

First, the history: In spite of today’s rosy nostalgia, evangelical Protestants have always felt themselves the targets of creeping secular attack. To pick just one example, when SCOTUS ruled against devotional Bible-reading in public schools in 1963, evangelicals responded with apocalyptic alarm.

In the pages of leading evangelical magazine Christianity Today, for example, the editors intoned that the decision reduced Christian America to only a tiny “believing remnant.” No longer did the United States respect its traditional evangelical forms, they worried. Rather, only a tiny fraction of Americans remained true to the faith, and they had better get used to being persecuted.

Similarly, fundamentalist leader Carl McIntire insisted that the 1963 school-prayer decision meant the death of Christian America. In the pages of his popular magazine Christian Beacon, one writer warned that the Supreme Court decision meant a wave of “repression, restriction, harassment, and then outright persecution . . . in secular opposition to Christian witness.”

From the West Coast, Samuel Sutherland of Biola University agreed. The 1963 decision, Sutherland wrote, proved that the United States had become an “atheistic nation, no whit better than God-denying, God-defying Russia herself.”

But! We might say that those conservatives were wrong, but today’s might be right. As Ken Ham warned his Twitter followers this morning, perhaps “It’s coming!” Maybe New York’s new gender law really will put conservative evangelical pastors in a legal bind.

After all, it is not only radical young-earthers who are concerned. Conservative pundits such as Rod Dreher have similarly warned of the creeping overreach of today’s secular gender ideology.

And in some ways, as higher-ed watchers like me have noticed, changes really are afoot. Institutions such as universities that rely on federal student-loan dollars to stay afloat might face intense pressure to comply with anti-discrimination guidelines.

But will a preacher ever be pulled out of his pulpit for “preach[ing] faithfully from God’s Word that there’s only two human genders God created”? No. That’s not how religious discrimination works in the USA. Just ask any historically persecuted minority.

For example, the federal government has long shelled out huge subsidies to farmers, including hog farmers. Does that mean that religious preachers who tell their audiences that eating pork is sinful are “arrested for hate speech”? No.

Similarly, the federal government has funded school textbooks that teach basic chemistry. They teach that the core of a substance is determined by its molecular makeup. Does that mean that Roman Catholic priests who tell parishes that wine has been transubstantiated into blood are “arrested for hate speech”? No.

Or, to take the most painful 20th-century example from the world of evangelical Protestantism, when the federal government passed legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, were white evangelical preachers ever stopped from including racist content in their Sunday sermons? No.

In spite of what alarmist preachers might say, the problem for conservatives won’t be about their pulpits. When they want to refuse service to same-sex couples or refuse admission to transgender students they might have to deal with a new legal reality.

But the idea that the amped-up gender police will storm into churches to arrest pastors is more Thief in the Night than Queer Nation.

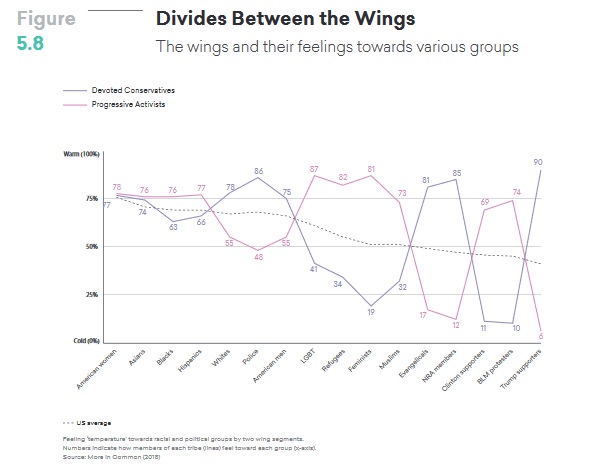

They didn’t ask specifically about creationism, but their findings translate well. As I’m arguing in

They didn’t ask specifically about creationism, but their findings translate well. As I’m arguing in