When I saw the headline, my nerd spidey-sense tingled. I was excited to read about the history of conservative anti-college feelings. But when I read the whole article, I was struck once again by the half-baked nature of the claim. Once again, a smart, well-informed pundit who claims to be examining culture-war history stops half-way. When will we start looking beyond the 1960s?

An earlier generation also worried…

Here’s the dilemma: at The Atlantic, Jason Blakely recently promised to explain the history of recent GOP ire against higher education. Looking at the current proposed tax plan, for example, it seems as if some members of Congress are out to punish elite universities.

Blakely argues that this conservative resentment of higher education has historical roots. In his analysis, he makes some vital points. Most powerfully, he notices that conservatives seem to mistake a very small segment of higher education for the higher-educational landscape as a whole. As he wisely puts it,

conservative anxiety is best expressed as being about a small set of marquee positions of honor and prestige in the liberal arts that happen to be largely staffed at present by those whose political commitments lean left.

That’s a vital point that is too often ignored. “College” as a whole is not particularly leftish…or even particularly anything. The crazy-quilt patchwork of colleges, universities, and other post-secondary institutions is wildly disparate. It is an absolutely vital notion that people just don’t seem to want to notice. Kudos to Blakely for emphasizing it. But when he proposes to analyze the history of this conservative anger toward elite universities, he puzzlingly only scratches the historical surface. After a nod to the “deep and complex historical roots” of anti-intellectualism in American culture, he argues that

the trope of portraying American universities as a threat to society emerged with particular intensity in the 1970s and ‘80s.

He looks at the work of neoconservatives such as Irving Kristol and Allan Bloom regarding “what they saw as the moral laxity and corrosiveness of the 1960s counterculture.”

Fair enough. And interesting, as far as it goes. But what Blakely and other writers miss is the longer relevant history of this specific trend in culture-war thinking.

As I argue in my book about educational conservatism, if we hope to make any sense of today’s conservative anger at elite higher ed, we can’t start with the 1970s. We need to begin in the 1920s, when conservative intellectuals had their first experience of exile, when the tropes exploited so powerfully by Kristol and Bloom were first developed.

It was not in the 1970s, but in the 1920s that conservatives developed their deep abiding anxiety about trends in elite higher education. Consider a couple of examples.

In the early 1920s, for example, anti-evolution celebrity William Jennings Bryan railed against trends in American higher education. In one public dispute with University of Wisconsin President Edward Birge, for example, Bryan offered the following memorable proposal. If universities continued to promote amoral ideas such as human evolution, Bryan suggested, they needed to post the following notice:

Our class rooms furnish an arena in which a brutish doctrine tears to pieces the religious faith of young men and young women; parents of the children are cordially invited to witness the spectacle.

Elite schools, Bryan warned, had begun actively to teach “moral laxity and corrosiveness.” Universities needed to warn parents that they no longer taught students right from wrong. This sense of conservative outrage at higher-educational trends was a driving force behind the culture wars of the 1920s.

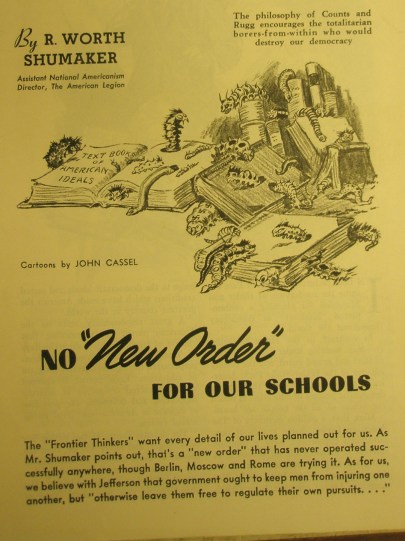

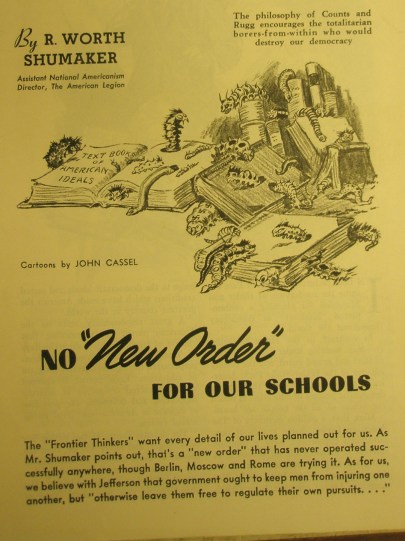

It wasn’t only Bryan and it wasn’t only evolution. Since the 1920s, conservative intellectuals have voiced “with particular intensity” their sense that elite universities had gone off the moral rails. Consider the case made by some patriotic conservatives in the 1930s and 1940s against the anti-American direction of the elite higher-educational establishment.

In 1938, for instance, Daniel Doherty of the American Legion denounced elite institutions as mere “propagandists.” Universities such as Columbia had taken to “attacking the existing order and [to] disparagement of old and substantial values.”

These intense antagonistic feelings toward elite universities were widely shared among conservative thinkers in the 1930s. Bertie Forbes, for example, syndicated columnist and founder of Forbes magazine, warned that elite schools were “generally regarded as infested” with subversive and anti-moral professors.

When we talk about our culture-war history, we can’t short out these voices from the 1920s and the 1930s.

Why not? If you are purporting to explain the history of an idea, you can’t only focus on the most recent articulation. It implies that these questions began to rankle only in the past fifty years, instead of slow-cooking for about a century now. The radicalism of the 1960s, and the reaction of the 1970s, were not new. They did not create new terms of culture-war angst, but rather only perpetuated existing themes.

This is not only a nerdy quibble but a fundamental part of culture-war politics. Think of it this way: When Irving Kristol and Allan Bloom made their arguments in the 1970s—the ones Blakely thinks inaugurated conservative anger at elite universities—they did not need to convince their conservative audiences of their central point. Conservatives had a vague but powerful sense that elite intellectual institutions had long since turned against truth, goodness, and beauty. Convincing someone of something they already believe to be true is a much easier task.

I don’t mean to single Blakely out. He’s not the only writer to woefully misrepresent America’s culture-war history. Plus, I’m not saying that historians can’t cut off their arguments at some reasonable point. We don’t all need to always write about everything. I get that. In a case like this, however, ignoring the vital and intensely relevant precursors to the 1970s history is not okay. We end up with a misleading notion of the genealogy of conservative outrage. We end up thinking we understand something we haven’t really even begun to understand.