It might seem sloppy or even a little slapdash. Historians claim to know things about the past, but most of us don’t have hard-and-fast proof for the arguments we make. This morning I’d like to share one small example of the way the process works, at least in the case of my upcoming book.

I just finished reading John Lewis Gaddis’s Landscape of History with my graduate class. Gaddis is a leading historian of the Cold War. In Landscape of History, he argues that academic historians don’t try to make the same claims as social scientists. And that’s okay.

Gaddis uses a painting of a wanderer looking down on a fog-cloaked valley to illustrate his point. Historians can never be absolutely sure of their data; they are like the wanderer—looking into a distance that is cloaked and ultimately mysterious. Some social-scientists might object that the process makes claims it can’t back up with real data. Gaddis describes one such encounter:

Some years ago I asked the great global historian William H. McNeill to explain his method of writing history to a group of social, physical, and biological scientists attending a conference I’d organized. He at first resisted this, claiming that he had no particular method. When pressed, though, he described it as follows:

“I get curious about a problem and start reading up on it. What I read causes me to redefine the problem. Redefining the problem causes me to shift the direction of what I’m reading. That in turn further reshapes the problem, which further redirects the reading. I go back and forth like this until it feels right, then I write it up and ship it off to the publisher.”

McNeill’s presentation elicited expressions of disappointment, even derision, from the economists, sociologists, and political scientists present. “That’s not a method,” several of them exclaimed. “It’s not parsimonious, it doesn’t distinguish between independent and dependent variables, it hopelessly confuses induction and deduction.”

Gaddis liked the method anyway, and so do I. As I’m reviewing my research files for my upcoming book about the history of evangelical higher education (available for preorder now!) I came across a few items that didn’t make the final cut, but they do help illustrate the way I came to make the arguments I’m making.

One of the central arguments of the book is that evangelical and fundamentalist colleges have always been subjected to furious scrutiny from the national network of fundamentalists. There has always been a strong sense among the evangelical public that evangelical colleges must be held to a high standard of religious purity. Naturally, parents and alumni of every sort of college watch their schools closely. After all, they might be spending big bucks to send their kids there. In the case of evangelical higher education, even unaffiliated busybodies feel entirely justified—even compelled—to intrude.

Another key argument of the book concerns the feud between the fundamentalist and evangelical branches of the conservative-evangelical family. Beginning in the 1940s and 1950s, the fundamentalist network split into fundamentalist and new-evangelical camps. Some historians have called this a “decisive break” or an “irreparable breach,” but at institutions of higher education, it always felt more like a continuing family feud. At least, that’s the argument I make in the book.

How do I know?

As Professors McNeill and Gaddis insist, it is mostly a question of time. I spent long hours and days in the archives of various schools. I read everything. As I did so, ideas about these themes developed. As they did, I went back and reread everything. Did the idea seem to match the historic record? Over and over again, I noticed that school administrators fretted about the eternal and invasive fundamentalist scrutiny to which they were subjected. Over and over again, I noticed the tones of betrayal, hurt, and intimate outrage that characterized the disagreements between “fundamentalist” and “evangelical” schools.

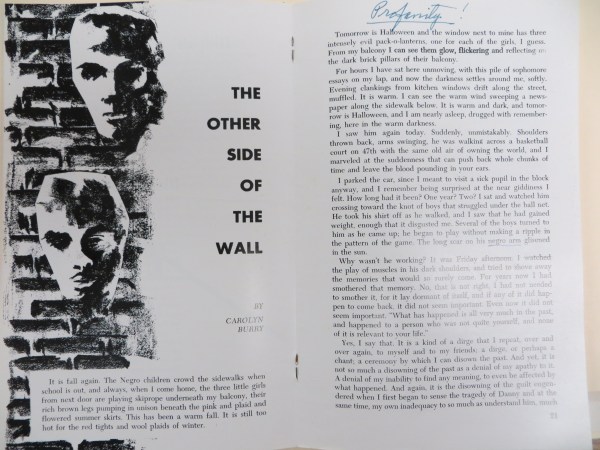

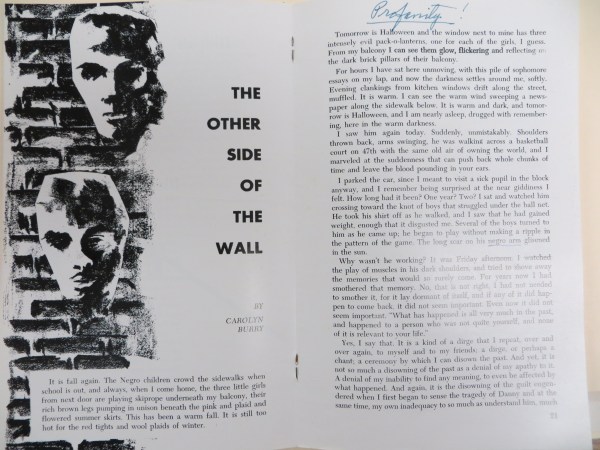

Not all the evidence made it into the book. One episode I do discuss is a controversial student publication from Wheaton College in Illinois. Back when he was an earnest evangelical student in the early 1960s, Wes Craven—yes, the Nightmare on Elm Street guy—was the student editor of Wheaton’s literary magazine. As part of his intellectual revolt against fundamentalism, Craven published two stories that he knew would ruffle fundamentalist feathers. In one, an unmarried woman wonders what to do about her pregnancy. In another, a white woman is sexually attracted to an African American man.

A quirk of the archives helped me see the ways the controversy unfolded. At the time Craven’s magazine came out, Gilbert Stenholm had been working at fundamentalist Bob Jones University for quite some time. He kept everything. His archive files are full of unique documents that helped me see how fundamentalist higher education worked in practice.

For example, he saved his copy of Craven’s controversial student magazine. His notes in the margins helped me understand the ways fundamentalists were outraged by their new-evangelical cousins. Along the edges of one story, an outraged Stenholm penned in one shocked word: “Profanity!” Elsewhere, Stenholm filled the margins with exclamation points.

What did this one-of-a-kind archival find tell me? It helped me see that fundamentalist schools like Bob Jones University had never really washed their hands of evangelical schools like Wheaton. For Stenholm, at least, the goings-on at Wheaton were always of intense interest. And it helped clarify to me the ways members of the far-flung fundamentalist community watched one another. They were always nervous about slippage—always anxious that trustworthy schools could slide into the liberal camp.

Stenholm’s outrage in the case of Craven’s student magazine didn’t make the book’s final cut, but this copy of Wheaton’s student magazine in Stenholm’s collection told me a lot. It doesn’t serve as the kind of “parsimonious,” independent-variable method that Gaddis’s social scientists would prefer. But taken all together, bits and pieces of archival gold like this one guided me to the argument I finally “ship[ped] . . . off to the publisher.”