How can schools save America? The answer is clear, but nobody wants to hear it. New research piles on more evidence that our deeply cherished notions about schooling and social fairness just don’t match reality.

If a tree grew in the forest and there was no one around to hear it, could it still serve as an awkward metaphor?

Try it yourself: Whatever your politics, don’t you think every kid deserves a good education? I do. And part of the reason is because a good education can help children secure better jobs. For children from low-income homes, those jobs can pull families out of poverty into the middle class.

It’s not just a myth. We all know people for whom this story has proven true. Like a lot of people in the aftermath of World War II, my father came to this country with nothing. Because he went to good, free public schools in New York City, including City College of New York, he was able to become an electrical engineer and send me to college, too.

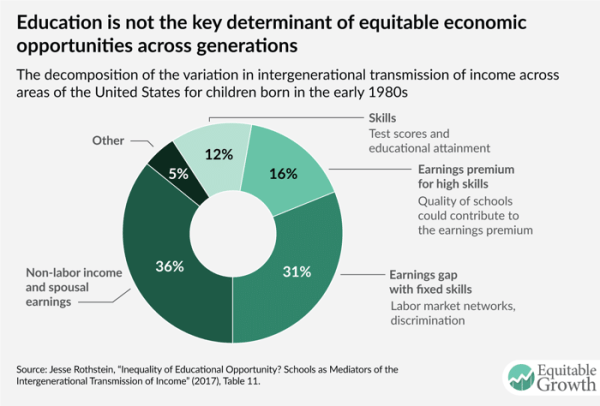

As Rachel Cohen describes in the new Atlantic, however, research from Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein suggests that these rags-to-richer-through-school stories are not the norm. As Rothstein describes,

There is thus little evidence that differences in the quality of K-12 schooling are a key mechanism driving variation in intergenerational mobility.

For people like me, this conclusion is hard to hear. We go into teaching and education, after all, because we hope to contribute our mite to making the world a better place. We work hard with kids from lower-income homes to help them succeed in school and get into and through college. And we do it all in the hopes that students might be able to get good jobs. Long term, we hope today’s striving students will build tomorrow’s stable, prosperous communities.

Is it all a myth?

According to Rothstein, factors besides formal education have more to do with economic mobility. As he concludes,

most of the variation in CZ [“commuting zones”] income mobility reflects (a) differences in marriage patterns, which affect income transmission when spousal earnings are counted in children’s income; (b) differences in labor market returns to education; and (c) differences in children’s earnings residuals, after controlling for observed skills and the CZ-level return to skill.

In other words, good schools can help people move up, but they’re not the main factor. More important factors include the number of single-parent families in a neighborhood, the availability of jobs, the presence of unions, and hiring discrimination.

No doubt we’ll be able to have some unproductive culture-war shouting matches over these findings. Cultural conservatives will point to the importance of traditional marriage patterns. As Professor Amy Wax did recently, they might urge people to embrace “bourgeois culture” as a ticket out of poverty.

Progressive types like me will underline the primary importance of non-discriminatory hiring practices and strong unions.

All of us, though, will probably miss the central point. Focusing on school reform instead of social reform is backwards. We might think of this as the “birch-on-boulder” dilemma. Around these parts, a five-minute walk in the woods will show you plenty of examples of bold birch trees growing out of big boulders. The tree’s roots heroically scramble to reach scanty soil. Even though the baby trees started on top of rocks, they were able to somehow overcome those conditions and grow up tall and strong.

There is no doubt that some trees can thrive even in the most difficult conditions. If we want to grow trees, however, we wouldn’t plant all of them on top of boulders and offer some of them a little more soil or fertilizer. Instead, we would start by clearing out the boulders, preparing rich soil beds for all the trees.

Similarly, if we want to help young people rise above their difficult social conditions, we shouldn’t just put a few more computers in a couple of schools or tinker with a couple of difficult-to-find programs that might help a few students get an advantage in their educations. Instead, we need to make it so that all students have good conditions for growth. We need to clear away the “boulders” of hiring discrimination, job deserts, weak unions, and reduced family resources.

In the end, we face a sobering answer to the question. How can schools save America? They can’t. At least not by themselves.