You know the script: Progressives face off against conservatives, fighting over history textbooks. Progressives want more focus on freedom struggles, conservatives on America’s exceptionalism. It’s the story we hear a lot, and one I focused on in my book about educational conservatism. My reading these days, though, points out the hidden importance of a very different sort of textbook battle.

As do a lot of academic types, I spend my summers catching up on reading. I often agree to write reviews of new books for a variety of academic journals. This summer, I’m reading historian Charles W. Eagles’ new book Civil Rights, Culture Wars: The Fight over a Mississippi Textbook.

It’s a terrific book. If you want to read my full review, you’ll have to wait til it comes out in the Journal of American History. In these pages, I’d like to talk about something else, something I don’t have room for in my official review, one of the most revealing and eye-opening parts of Eagles’ history.

Professor Eagles tells the story of a new state-history book for Mississippi, Mississippi: Conflict and Change. It was an effort by sociologist James Loewen and historian Charles Sallis in the early 1970s to bring a more balanced and more progressive history to Mississippi’s ninth graders.

Eagles tells the story of the controversial book in remarkable detail, and the usual players all show up. Progressives liked the book for finally including African Americans in the history, not only as loyal slaves or bumbling Reconstruction-era politicians, but as Mississippians. Conservatives blasted the book as unbalanced, obsessed with denigrating the history of the great state of Mississippi.

As I followed the predictable back-and-forth, I couldn’t help but hear an additional muted counter-melody running through all the deliberations. There was an additional voice struggling to be heard, a point of view beyond the usual culture-war progressivism and conservatism.

Over and over again, the experienced teachers who reviewed and rejected Loewen’s and Sallis’s textbook made a similar complaint. The book was no good, they argued, not because of any overarching ideological slant, but for a much more pragmatic reason. Any boasts about the academic excellence of the history or about its progressive ideology were simply beside the point.

Using this textbook, the teachers wrote, would make it impossible for Mississippi teachers to do their jobs.

Why?

Because the content of the textbook would unsettle classrooms. It would make it impossible for teachers to do any teaching at all, since teachers would instead be breaking up fights among students.

Consider, for example, the remarkable testimony of textbook-review board member John Turnipseed. The book was “unsuitable for classroom use,” Turnipseed concluded, because “in a racially mixed classroom, the discussion of the material would be improper. . . . [it] would cause harsh feelings in the classroom.”

The judge in the federal case could hardly believe his ears. Judge Orma Smith asked Turnipseed if Turnipseed really thought images and discussions of lynching could be left out of a Mississippi history book.

Judge Smith: “You don’t see any historical value in that kind of situation?”

Turnipseed: “No sir, I don’t. I feel the contributions made by blacks as well as whites are more important and should not be degraded.”

Smith: “The racial situation that existed wouldn’t have had any historical significance at all? Where are students to learn the fact if they don’t learn them in school?

Turnipseed: “Again, I think in integrated classrooms it would cause resentment.”

Just as historian Jonathan Zimmerman argued in his landmark book Whose America, school leaders always prefer to add in bland praise, rather than to suggest any criticism. Every social group demands that their history be praised, and school leaders like Turnipseed usually acquiesce. To do anything different would unsettle classrooms in a dangerous way.

It was not only white conservative board members like John Turnipseed who focused on the goal of quiet classrooms. African American board member John Earl Wash also voted against the Loewen and Sallis book. Images of lynching, Wash argued, hurt African American students. “The 9th grade black student,” Wash wrote, “would probably resent hearing about the lynching topic.”

Even though Loewen, Sallis, and their fans envisioned their new textbook as a corrected, pro-civil-rights history, experienced teachers like Wash had different worries. Topics such as the Ku Klux Klan and lynching, Wash testified, were things Mississippi African Americans “want to forget.” Worst of all, the progressive textbook put African-American students in physical danger. In Wash’s words,

Blacks just resent anything that I would say would carry them back to times of slavery, anything. Then anything to do with the Klan or terrorizing blacks or something of this nature, right, it would definitely bring conflict.

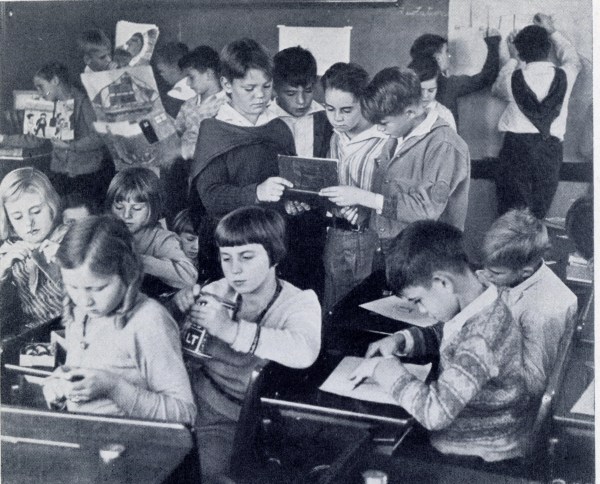

In racially mixed classrooms, talk of lynching and Klan violence threatened to do more than simply educate young students. As experienced teachers knew, talk of violence could quickly become real violence, putting minority students in the crosshairs.

In 1970s Mississippi, at least, there were other reasons for opposing progressive textbooks than mere knee-jerk traditionalism. Teachers knew that the topic was explosive among students. If they hoped to control their classrooms, they didn’t dare expose students to controversial ideas, even if they agreed that those ideas were true and important.

olar. Who will it be?

olar. Who will it be?