Is there a democratic way to decide difficult technical questions? Last week, voters in Greece soundly defeated a complicated economic proposal. For those of us interested in educational culture wars, it raises an interesting question: Could we vote on evolution?

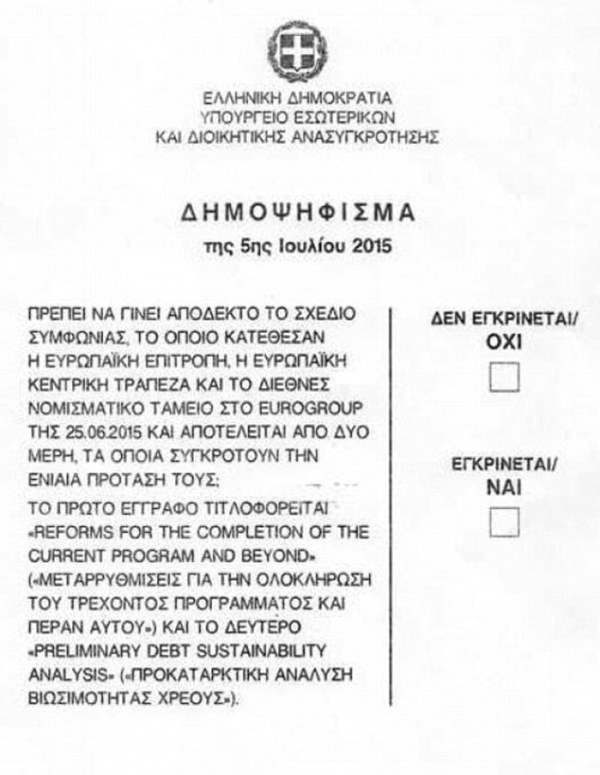

In Greece, voters faced a dauntingly worded ballot. In English, it read as follows:

Should the deal draft that was put forward by the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the Eurogroup of June 25, 2015, and consists of two parts, that together form a unified proposal, be accepted? The first document is titled ‘Reforms for the Completion of the Current Programme and Beyond’ and the second ‘Preliminary Debt Sustainability Analysis.’

Hrm? What would an “oxi” vote mean in this case? “Nai?”

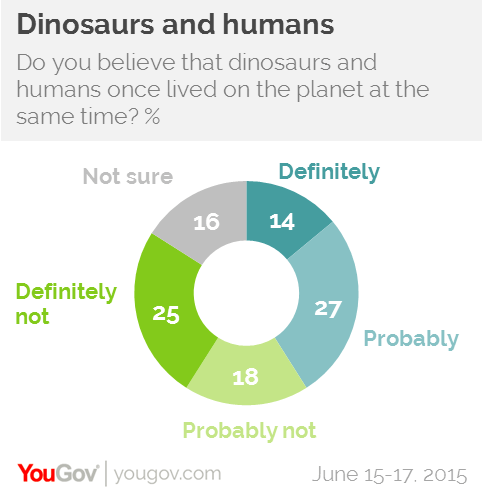

Of course, the SAGLRROILYBYGTH will say that voters could simply look up the two documents and decide intelligently if they deserve support. But to think that most voters would do that seems woefully naïve, or perhaps refreshingly optimistic. In the United States, after all, poll data suggest that large numbers of Americans think that humans and dinosaurs lived side-by-side, and, as Rick Shenkman has pointed out, most of us don’t know basic facts about our government and society.

Many Greek voters, similarly, seemed to have only a tentative grasp on the question at hand. Instead of voting on the specifics of either of the reform plans, Greeks likely voted based on their impressions about the two sides of the issue. Voting “yes” was generally perceived to be a vote in favor of the euro, and against the leftist policies of the ruling Syriza party. A “no” vote, in contrast, was often seen as a vote against economic austerity and in favor of Syriza. Even more confusing, some voters seemed to think that a “yes” vote meant taking pride in Greece’s place as a European nation, while others thought a “no” vote was the way to express Greek national pride.

Even after the vote, the results are confusing. Will the government now negotiate for an economic bailout? Will the government accept austerity measures after all as a condition?

One thing seems clear: many Greek voters used the referendum as a way to express something about who they were, whom they believed, rather than as a way to make a specific policy choice.

When it comes to evolution and creationism, we see similarly confusing commitments. Support for creationism remains high, not because people have not heard of evolutionary science, but because people want to show their support for traditional religion.

As Dan Kahan of Yale Law School puts it so well,* our positions on evolution/creation tell us about who we are, not about what we know. People who say they “believe in” evolution do not actually know any more about it than people who say they do not.

With all this in mind, could we imagine a scenario in which America voted on evolution? What would such a referendum look like?

These are preposterous questions in many ways, but bear with me for a minute. We’ve seen time and time again that large percentages of Americans believe that humanity has been created fairly recently. We’ve also seen that large percentages of Americans favor teaching evolution and creationism/intelligent design side-by-side in public schools. What if we tried to agree upon our school curriculum in a democratic way, by holding a national referendum on the issue?

It seems to me the wording of such a ballot might be crucial. If we asked voters, for instance, to vote on whether they thought evolution was true, we’d likely have a huge negative result. Americans just don’t want to agree to that, for a host of religious and cultural reasons.

But what if we asked voters if they wanted public schools to teach the best available science? And what if we asked voters if they believed most scientists thought evolution was the best scientific explanation of the development of life?

As I argue in an upcoming book, the wording could make a big difference. What do we really want our public schools to teach about evolution? Do we need children to believe that evolution is true? Or, rather, do we want to insist that children have a deep understanding of the science of evolution?

We can do more than guess. In 2012, the National Science Board experimented with two similar questions about evolution. When they asked respondents if “human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals,” just under half (48%) said “true.” But when they changed the wording, that percentage leaped. When they asked people if “according to the theory of evolution, human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals,” a whopping 72% of respondents agreed.

What if we were to vote on evolution? To my mind, if we did something like that, the ballot should have two simple questions:

1.) Do you want public schools to teach the best available science? And

2.) Do you think that scientists say humans evolved from other species?

With questions like that, we would get a whopping public voice of support for teaching evolution in public-school science classes.

*Exciting update! Professor Kahan has firmed up the date for his visit to our scenic campus. He’ll be giving his talk to our Evolution Studies Program on Monday, February 22, 2016. Good seats still available!