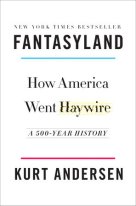

It’s more than just a couple of minor goofs. A recent “retro” report about creationism and evolution education in the New York Times makes the usual huge mistakes in its description of American creationism.

SAGLRROILYBYGTH know I’m no creationist myself. I want more and better evolution education in America’s public schools, as I argued recently in my book with philosopher Harvey Siegel. But we won’t achieve that goal as long as we keep telling ourselves these comfortable/scary myths about creationism. If we want to fight the political influence of creationism, it is far better to understand creationism as it really is, instead of the clumsy monstrosity we usually imagine.

Kicking ass for creation.

Let me start with the positives. The report did a good job of describing the basic history of anti-evolution legislation and court battles from the 1920s to today. As they describe, anti-evolution laws have been struck down by SCOTUS and other courts time and time again. They also did well to include the voices of both the smartest pro-evolution pundit—Brown’s Kenneth Miller—and leading creationists, including Answers In Genesis’s Georgia Purdom and a panel from the intelligent-designing Discovery Institute.

The problems with the report are not mere details or minor interpretative mistakes. No, the danger is that too many of us non-creationists woefully misunderstand the world of American creationism. As with this report from the New York Times, we will repeat misleading notions to ourselves and think we have a better picture of creationism. The real danger, of course, is that we will traipse off with our non-knowledge to make plans and policies, without a whiff of a sense that we are building on the wrong foundation.

As I’m arguing in my current book about American creationism, the first goof most non-creationists make is to treat creationism as a large, scary, undifferentiated mass. In the NYT report, for example, the young-earth Georgia Purdom is cited alongside the intelligent-designing Stephen Meyer as if there is not an enormous difference between their two beliefs.

Why does it matter? For one thing, the suggestion that a huge army of creationists are massing to take control of public schools is scary. But the idea of a fractured and disputatious set of cranky creationists isn’t. And that’s much closer to the truth. Consider, for example, Dr. Purdom’s criticism of intelligent design. While some evangelicals might like the notion at first, Purdom has argued, in the end, in an ID universe,

God appears sloppy and incompetent, if not downright vicious.

For the young-earthers at Answers In Genesis, ID is not an ally but rather another danger to be confronted. In the end, there is no such thing as “creationism”—at least not the way the New York Times article suggests. Rather, there are many creationisms. And those different visions of science and religion often fight one another far more viciously than they fight against mainstream science.

Here’s my second beef. As always, this article and its expert talking heads refer to creationism as “anti-science.” It’s not. All of us love science. As anthropologist Chris Toumey put it in his underappreciated book, God’s Own Scientists, creationists are like all Americans. We all have deep faith in the

plenary authority of science; that is, the idea that something is more valuable and more credible when it is believed that science endorses it.

In other words, whether people are shilling toothpaste, NASA budgets, or creation science, they always dress up in lab coats to make their pitch.

Why does that matter? If there are two simple sides to these culture war fights—science on one side and anti-science on the other—then we would have a much simpler time convincing the antis to get on board. Instead, as we saw so excruciatingly in the Ham-on-Nye debate a while back, what we end up doing instead is wasting time with each side trying to prove just how much it loves science. We don’t need to have that talk again. If we all love science, we can have more productive conversations—even if we disagree—about how to teach science in public schools.

Read this!

Last and most important, we need to acknowledge the false and misleading myths about creationism’s history. This article is especially egregious in suggesting that creationism is making a bold new political advance, that fundamentalist armies are sweeping state legislatures in a frightening new show of creationist strength.

For example, the NYT report says that creationists haven’t scored a victory since the Scopes trial in 1925, until now. It describes menacingly that a “growing skepticism about science has seeped into the classroom.” I understand the reasons for alarm, but the notion of a huge uptick in creationist political power simply does not match the historical record.

The career of anti-evolution agitation has been one of steady decline in ambition and reach. For nearly a century now, anti-evolution activists have fought for a set of ever-shrinking goals. As I found in my first book, anti-evolution laws in the 1920s wanted nothing less than the imposition of theocratic rule on American public schools. In Kentucky, for example, a 1922 bill would have banned not only evolution, but atheism and agnosticism. An amendment would have pulled any book from a public library that might lead a student to question her religious beliefs.

Compare those bills to creationists’ efforts today. Please don’t get me wrong. I am in full agreement with Kenneth Miller and Zack Kopplin; today’s anti-evolution laws are terrible. But that doesn’t mean that they represent a bold new surge of strength for anti-evolutionism. They don’t. Rather, they are just the latest strategic grab at scraps of influence and power by anti-evolutionists.

Why does it matter? Well, I think I probably don’t need to spell it out, but I will. If creationism is 1.) united, 2.) anti-science, and 3.) surging to greater and greater power, those of us who oppose religious imposition in public schools need to take drastic action. We’d need a wholesale reorganization of the decision-making process in public-school curricula. We would need to come up with radical ways to intervene in local educational decisions, as the US did with racial segregation to such mixed results.

If, on the other hand, creationism is shrinking, fragmented, and in agreement about the fundamental intellectual power of capital-S science, we face a much different environment. It won’t generate as much attention, but it would be better policy to simply continue our efforts. We should continue to do what we’ve been doing: Advocate tirelessly for more and better evolution education; explain and explore the real contours of American creationism; repeat that evolution is not a religious idea—it won’t hurt students’ religious faiths.