Okay, I admit it. I’ve been watching Orange Is the New Black. And I like it. But one episode I saw the other night included a painful example of what I’ve been calling the “missionary supposition” of anti-religious folks.

Orange Is the New Hack

First, a short introduction for those readers with better things to do: The show follows the prison career of a privileged woman as she serves her time. At first, I didn’t want to watch it. It sounded too much like the terrible genre of ‘brave excursions outside the gated community,’ ignorant self-righteous claptrap along the lines of Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed.

But after a couple of episodes, I was hooked. The protagonist’s story of elite woe is not as central as I feared. Each of the incarcerated women has her own story and the show makes the most of each.

**SPOILER ALERT: The following contains info about the end of season 1. And some bad language.**

Just because I watch, though, I can’t help but protest some of the stupid blunders incorporated into the story. In a couple of episodes, the protagonist, Piper Chapman, goes a few rounds with fellow inmate Tiffany “Pennsatucky” Doggett. In the show’s depiction of Doggett and in Chapman’s high-handed attitude toward Doggett’s religiosity, we see the worst sort of anti-religious bigotry and ignorance.

Religious = Psychopathic

I don’t have much of a problem with the show’s scathing depiction of conservative evangelical religion. We see this most frighteningly in the character of Doggett. Doggett is the unofficial leader of the charismatic Bible group at the prison. She leads deluded healing services and peppers her speech with Biblical references. Not only is Doggett portrayed as a snaggle-toothed, closed-minded, ignorant hillbilly with a heavy penchant for krazy, she actually only won her role as religious prophet by shooting an abortion-clinic worker out of petty spite.

Now, if this show wants to depict religious people that way, fair enough. It is embarrassingly biased, but if the show wants to take that kind of anti-conservative-religion slant, so be it.

But it’s harder for me to swallow the wildly ignorant understanding of religion from one unfortunate scene in the episode “Fool Me Once” [season 1, episode 12, about 55 minutes in]. Pennsatucky wants to baptize Chapman in the laundry sink. At that point, Chapman unleashes her real opinion about the whole thing. IMHO, the following scene demonstrates a terrible misunderstanding of the nature of religious belief, non-religious belief, and the nature of America’s culture wars, not just on the character’s part, but by the makers of this show:

Chapman: Okay, nope, see, I can’t do this. I’m sorry. I really want us to get along. I do. But I can’t pretend to believe in something I don’t. And I don’t.

Pennsatucky: Chapman: We’ve all had our doubts.

Chapman: No, see, this isn’t ‘doubts.’ I believe in Science. I believe in Evolution. I believe in Nate Silver, and Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Christopher Hitchens, although I do admit he could be kind of an asshole. I cannot get behind some supreme being who weighs in on the Tony awards while a million people get whacked with machetes. I don’t believe a billion Indians are going to hell, I don’t think we get cancer to learn life lessons, and I don’t believe that people die young because God needs another angel. I think it’s just bullsh*t, and on some level I think we all know that, I mean, [addressing other Christians] don’t you?

Other Christian #1: [sheepishly] The angel thing does seem kinda desperate…

Pennsatucky: [threateningly, to OC#1] I thought you was a Christian.

OC #1: [defensively] I am, but I got. . . some questions. . .

Whooch! Didja see that? Again, I don’t have a beef if this show wants to malign religious conservatives, if it wants to depict anti-abortion activists as cynical, stupid, self-serving sociopaths. It’s an awkward hack job, IMHO, but not as bad as the wildly ignorant fantasy depicted in the scene above.

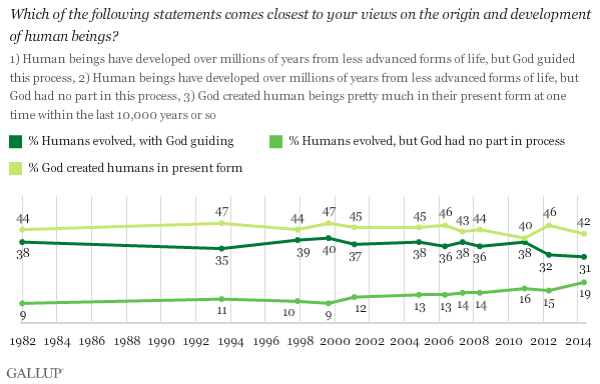

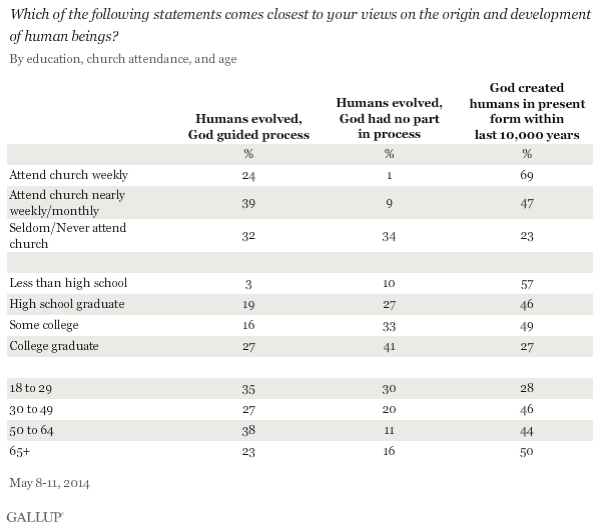

As I’ve argued in the pages of the Reports of the National Center for Science Education, too many anti-creationists show this same sort of ignorant “missionary supposition.” They think, along with Piper Chapman and the makers of this show, that the truths of anti-religion are so blindingly obvious that any (thinking) religious person must secretly share them.

Now, to be fair, I should point out that I do (roughly) share those beliefs. I believe in science. I believe in evolution. I like Neil deGrasse Tyson and I don’t think anyone is going to hell. But just because I agree doesn’t mean I can stomach the weirdly ignorant assumptions in which those statements are wrapped.

When Chapman recites her sophomoric list of village-atheist taunts, the gathered Christians are only kept from agreeing by the bullying of their psychopathic religious leader. In this sort of atheist fantasy, the truths of science only fail to conquer when hearers are not free to acknowledge their obvious awesomeness.

This attitude mirrors nothing so much as the overweening confidence of early religious missionaries. Many Bible missionaries in the early part of the twentieth-century, for example, assumed that the truth of the Bible was so overwhelming that anyone who caught a glimpse of its pages must be supernaturally converted. As a result, Bible missionaries spent a great deal of time and treasure to distribute the Gospel around the world.

At Chicago’s Moody Bible Institute, for example, evangelists distributed printed tracts and gospels throughout the nation and the world, based on this assumption about the supernatural power of Holy Print. As William Norton of the MBI’s Bible Institute Colportage Association related in 1921,

A man was given a tract by the roadside; simply glancing at it, and coming to a hedge, he stuck the tract into the hedge; but it was too late; his eyes had caught a few words of the tract which led to his conversion.

In this understanding of salvation and conversion, some truths have such power that the merest exposure to them is enough to convert the unwilling. Ironically, folks at places such as the Moody Bible Institute have gotten much more sophisticated in their understanding of conversion, while self-satisfied atheists like the makers of Orange Is the New Black apparently have not.

Among conservative evangelical Protestants these days, the difficulties of missionary work are more thoroughly appreciated. As conservative Christian educator David Harley wrote in 1995, missionaries must begin with a “sensitive appreciation of other cultures.” Missionaries who try to plunk down in the midst of a non-Christian population and simply begin spreading Truth amount to nothing more than “evangelical toxic waste,” Harley argued.

Actual missionaries no longer think they can convert without effort. They no longer tell each other to shout out the Gospel and count on it to spread itself. Rather, religious people show a more nuanced understanding of the ways people change their minds.

But there still seem to be people out there so ignorant of other cultures that they think they can convert the heathen with a simple exposition of the Truth. Folks who think that by declaiming a few holy names, such as Christopher Hitchens and Neil deGrasse Tyson, the scales will fall from the eyes of the benighted Christian multitudes.

Pish posh.