We Americans can’t stop fighting over our schools. Should we teach evolution? Can we teach kids about sex? Can students read literature that includes “mature” themes? Do schools need to teach kids to be patriots? For at least a century, these questions have roiled our culture-war waters. There is a better way to think about these fights. As we see in a sad recent news story, a profound AGREEMENT about schooling lurks beneath all of our culture-war battles.

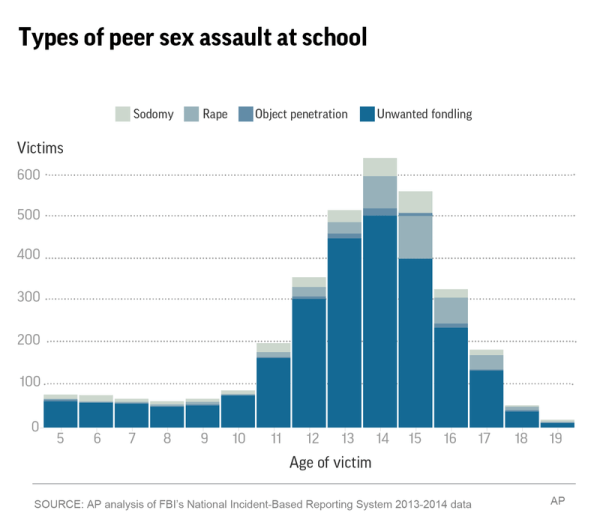

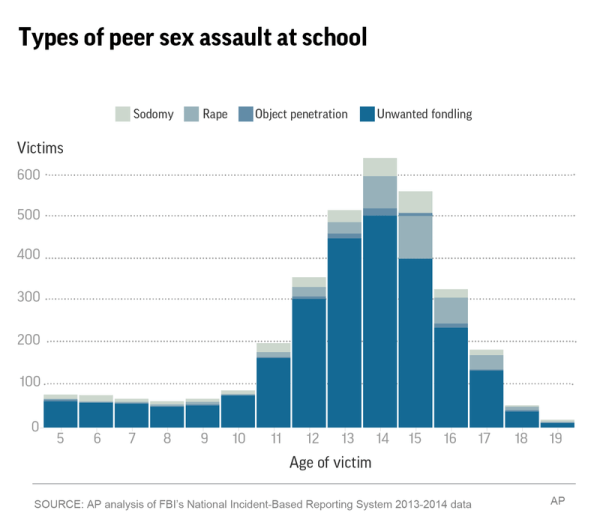

The news itself is grim: As reported by the Associated Press, over four years, America’s public K-12 schools logged 17,000 official reports of sexual assault among students. Not only are students targeted by other students, according to the AP story, but schools often downplay the seriousness of the dangers. Legally, schools are required to intervene to protect students. If sexual assaults took place among students, schools could legally be held accountable.

A dangerous place…

The story is troubling, but it points to the underlying fact about schooling that undergirds many of our culture-war battles. It is not only in the disturbing field of sexual assault, but in every area. No matter what our ideological or religious beliefs, we all tend to agree on one thing: Schools need to keep students safe. This assumption—often so widely shared that we don’t even need to mention it—has always played an influential role in our educational culture-war fights.

In the sexual-assault story, we see this often-implicit function of schooling come to the surface. As one academic expert said,

Schools are required to keep students safe. . . . It is part of their mission. It is part of their legal responsibility. It isn’t happening. Why don’t we know more about it, and why isn’t it being stopped?

I agree. But for a moment, let’s try to put our strong feelings about sexual assault to one side to consider the implications of this notion. If schools have an absolute mandate to keep children safe, how does that drive our discussions about common culture-war topics such as evolution, racism, and religion?

As I saw during the research for my book about educational conservatism, deeper arguments about student safety often drive the surface arguments about other topics. So, for example, when conservative activists oppose evolution education, they often do so on the grounds that evolution is a dangerous idea for kids. And, when progressives argue in favor, they say that students will be dangerously ignorant if they don’t learn real science.

Consider a couple of examples from 1920s battles over evolution education.

The fight in the 1920s began in earnest on the campus of my alma mater. Anti-evolution activist William Jennings Bryan wanted to clamp down on evolution education at the University of Wisconsin. Ever the sensitive populist, Bryan articulated one anti-evolution argument that played on this notion of student safety. If Wisconsin continued to teach evolution, Bryan noted sardonically, it should attach warning signs to each of its classrooms. What would they say?

Our class rooms furnish an arena in which a brutish doctrine tears to pieces the religious faith of young men and young women; parents of the children are cordially invited to watch the spectacle.

Pish-posh, evolution advocates responded. Savvy progressive politicians attacked the notion that learning evolution was somehow unsafe. As Fiorello LaGuardia argued in 1924, the only way to make sure that students were “safe in schools” was to make sure they were “learning to think.” Banning evolution, LaGuardia argued, was only “hysteria” that would hurt children.

The same assumptions about student safety energized school battles throughout the twentieth century. In the explosive school fight in Kanahwa County, West Virginia in the 1970s, for example, both sides assumed that schools must keep students safe. They disagreed about what that meant. Conservatives often argued that a new set of textbooks put students in danger, since the new books mocked traditional religion and threatened students’ souls. Progressives insisted that the new books kept students safe by helping them see different perspectives and encouraging them to think critically about religion.

At one turbulent school-board meeting in Charleston in 1974, activists made familiar arguments about student safety. The meeting was crowded. Speakers had to sign up in advance. The crowd booed progressives and cheered conservatives. Conservatives often suggested that multicultural textbooks threatened students by deriding their religious beliefs and eroding their faith. Progressives countered that students could only be kept safe by learning about people different from themselves.

Conservative leader Alice Moore at the packed 1974 school-board meeting.

For example, from the conservative side, PTA member Rory Petrie warned that the new books were “very objectionable” because they were “very subtly . . . undermining the religious beliefs of our children.” Similarly, concerned parent Robert Steckert warned that the books threatened his kids when they “cast doubt and skepticism upon my child.”

Progressives agreed on the goal of student safety. But they came to the opposite conclusion. Real student safety meant more, not less, cultural diversity. In order to keep students safe, the school board needed to make sure every student encountered different cultural perspectives. As one progressive parent and former teacher put it, the world was a complicated place. If students didn’t learn about the true diversity out there, they would be in danger. Yes, the real world could be a scary place, but the solution was not to be found in telling students that it was not. School needed to teach students about reality. As this parent put it, “we cannot hide it from our children.”

Another progressive activist from the West Virginia ACLU agreed. Students would be in danger unless they learned about the real world. Students needed to learn that different people saw things differently; students would only be safe if they acquired an “understanding of why people and groups of people are different.”

In all these school fights, whatever the apparent topic, the notion of student safety was paramount. All sides agree that students must be kept safe. All sides used the notion of danger to mobilize support for their positions.

And it continues today. When you hear rumblings of a culture-war battle in school, listen for it. Whether activists are ranting about sex ed or school prayer, evolution or Christian history, someone is sure to say it: Only my side will keep students safe.