Why would they do it?

These reactions seem extreme and mind-boggling. If we want to make sense of the new wave of repressive student activism on college campuses, we need to start with two not-so-obvious facts:

- Only a few college students actually behave this way—and there’s a pattern to it.

- There’s a long history to this sort of thing.

So, first, who are the students who are staging these sorts of shut-down-speaker protests? As usual, Jonathan Zimmerman hit the nail on the head the other day. Students at elite schools like his tend to be more aggressively united in their leftism. What seems normal at Penn and Yale, though, isn’t normal at most schools.

He’s exactly right. Richard Reeves and Dimitrios Halikias of the Brookings Institution crunched some numbers and came to the same conclusion. As they put it,

the schools where students have attempted to disinvite speakers are substantially wealthier and more expensive than average. . . . The average enrollee at a college where students have attempted to restrict free speech comes from a family with an annual income $32,000 higher than that of the average student in America.

The wonks at The Economist agree. “Colleges with richer, high-achieving students are likelier to see protests calling for controversial speakers to be disinvited,” they concluded recently. They even plotted an attractive three-color chart to prove it:

So it seems safe to say that richer students at fancier schools tend to be more likely to stage this sort of shut-up protest than college students in general. Of course, we don’t know for sure in every case, but the tendency is clear.

So what?

It adds a moral dimension to these protests that needs more attention. We’ve been down this road before.

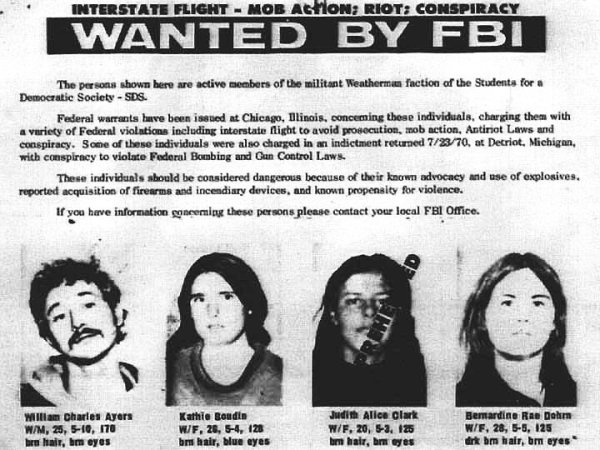

In the 1970s, a group of elite college students broke off from Students for a Democratic Society to form the violent militant group Weather Underground. They didn’t do much, but they wanted to. By the 1970s, the FBI was after them.

Okay, but did they contribute to the alumni fund?

They weren’t just run-of-the-mill college students. Bill Ayers’ father, for example, was CEO of Commonwealth Edison. Ayers the Elder even has a college named after him at my alma mater. That’s not something most Americans have experienced.

Bernardine Dohrn grew up in the tony Milwaukee suburb Whitefish Bay. (When I taught high school in Milwaukee, the kids jokingly referred to it as “White Folks’ Bay.” Ha.) She graduated from the super-elite University of Chicago. Clark also attended the University of Chicago. Boudin’s father was a high-powered New York lawyer and she went to Bryn Mawr College.

Their elite backgrounds and college experiences mattered. Weather rhetoric was flush with talk about their privileged status and the need for white elites to act violently.

In 1970, for example, Dohrn issued the Weather Underground’s first “communication,” a “DECLARATION OF A STATE OF WAR.” Rich white kids, Dohrn explained, had a “strategic position behind enemy lines.” They had a chance to strike from inside the belly of the beast. And they had a moral duty to act violently in support of world-wide anti-American revolutionary movements. It was time, Dohrn wrote, for rich white kids to prove that they were not part of the problem, they were part of the violent solution. As she put it,

The parents of “privileged” kids have been saying for years that the revolution was a game for us. But the war and the racism of this society show that it is too fucked-up. We will never live peaceably under this system.

Again…so what? What does this prove?

It helps us understand college protests that don’t seem to make common sense. Why would a group of college students assault a professor to protest against racism? Why would they react so ferociously to a seemingly innocuous comment about Halloween costumes?

Because—at least in large part—students from wealthy families at elite colleges are in a peculiar pickle. If they are at all interested in moral questions, they find themselves in a tremendously compromised moral position. They are the beneficiaries of The System. They are the ones who profit from America’s imbalanced racial and economic hierarchy. They enjoy their cushy lifestyles and glittering future prospects only because they were given an enormously unfair head start in life.

If you care at all about social justice, that’s a heavy burden to bear. One way to handle the strain is to go to extreme lengths to signal your rejection of The System. Though protests at fancy colleges may seem strange to the rest of us, they make sense if we see them as demonstrations of rejection, as proof of position. In other words, some students at elite colleges—at least the ones who do the reading—are desperate to demonstrate that they are not happy with racism, sexism, and class privilege. They need to show everyone that they are not lapdogs of the exploiters. Their protests are not only about changing policies, but about proving something about themselves. And those sorts of protests will necessarily swing toward extreme actions.

In the end, we will only scratch our heads if we try to figure out why liberal students insist on illiberal policies in terms of day-to-day political strategy. Instead, we need to see these protests as shouts of separation, desperate and ultimately ill-starred attempts to prove that students from the 1% are standing with the rest of us.