He did it! I don’t how it happened, but somehow President Barack Obama managed to accomplish one of the most dreamed-for educational goals of America’s social conservatives. During his presidency, that is, early teen sexual activity dropped significantly, according to the CDC.

I know, I know, it’s ridiculous to give Obama credit for something that merely happened to coincide with his time in the White House. But that’s what culture-war pundits do all the time. In this case, the numbers are pretty significant, and the cause is among those nearest and dearest to the hearts of American conservatives.

As I argued in my book about the history of educational conservatism, helping kids avoid the allure of premarital sex has always been one of the fondest educational dreams of social conservatives, especially conservative religious reformers. Why was evolutionary theory dangerous? If we taught children they were nothing but clever animals, they would certainly behave that way. Why was old-fashioned discipline important? Because children needed to learn to control their sinful, lusting nature.

I hate to do it, but let me quote myself here. When Alice Moore first joined the school board in Kanawha County, West Virginia in the 1970s, one of her first acts was to close down a progressive middle school. When I interviewed Moore I asked her about it. Here’s what I wrote in the book about Moore’s experience:

The school, Moore recalled, was not a proper learning institution. It had become a cesspool of unrestrained sloth and lust. The students, she recalled, did “whatever they wanted to.” As she walked in for her first inspection, a young couple stood in the doorway, wrapped in each other’s arms. She had to ask them to move out of her way, which they did only with notable resentment. Other students wandered around the school and neighboring fields, smoking and engaging in all kinds of sexual activity in nearby barns. When Moore asked the principal to explain this sort of behavior, he informed Moore that the school hoped to do more than simply transmit information to students; it hoped to transform them into agents of social change. Teachers should see their roles as co-learners, not as dictators.

This sort of progressive shibboleth exasperated Moore.

At the heart of warped progressive-ed thinking, Moore believed, was a mistaken notion of the nature of humanity. Lust needed to be schooled out of children, not winked and nodded at as a “natural” thing. Moore was not at all the only conservative activist to think this way. Consider William J. Bennett’s conservative index of cultural indicators. Bennett’s accusations were clear: Hippies had wrecked everything. Progressive attitudes in education had led to woeful increases in dangerous sexual activities among young people, in addition to crime, drug use, etc.

In short, for a hundred years now, educational conservatives have desperately dreamed of reducing the progressive dominance of “If it feels good, do it” attitudes among young people. And now, at long last, we seem to have some evidence that those dreams have come true, at least in part.

Here’s what we know: The excitingly named “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” from the Centers for Disease Control notes significant declines in sexual intercourse among America’s 9th and 10th graders (roughly 14- and 15-year olds). As the authors state,

Nationwide, the proportion of high school students who had ever had sexual intercourse decreased significantly overall and among 9th and 10th grade students, non-Hispanic black (black) students in all grades, and Hispanic students in three grades. A similar pattern by grade was observed in nearly half the states (14), where the prevalence of ever having had sexual intercourse decreased only in 9th grade or only in 9th and 10th grades; nearly all other states saw decreases in some or all grades. The overall decrease in the prevalence of ever having had sexual intercourse during 2005–2015 is a positive change in sexual risk among adolescents (i.e., behaviors that place them at risk for human immunodeficiency virus, STI, or pregnancy) in the United States, an overall decrease that did not occur during the preceding 10 years.

Why? We don’t know. And of course I’m kidding when I give President Obama credit. There are some things we can confidently predict, however. First of all, I don’t think we’ll see pundits shouting about this good news. As we’ve lamented here at ILYBYGTH in the past, good news about America’s schools and youth just never gets headlines.

Second, the warped popular myths about America’s public schools will continue to dominate. Gallup polls make it startlingly clear: When people know public schools, they like them. But when they describe public schools in general, people call them terrible. The notion that America’s public schools are cesspools of drugs, sex, and sloth is not true, but it is very widely held. Similarly, this data about trends in youth culture will not likely change people’s assumptions about schools and youth.

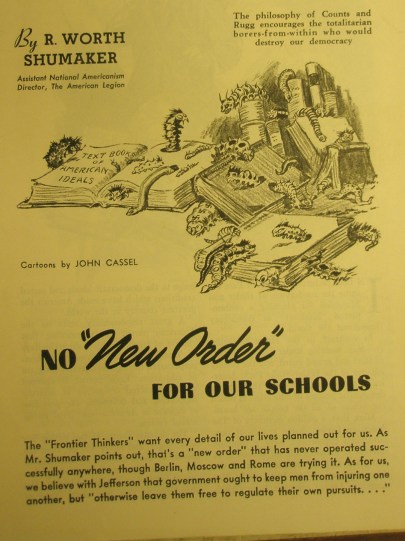

Finally, this student data points out yet again that the common story about the history of American public education is just not true. Many of us assume that progressive types took over public education back in the 1930s. We think that since the 1930s (or maybe since the 1960s) public schools have been dominated by progressive educators from fancy teachers’ colleges and think tanks. It’s just not true. Throughout their existence, public schools have reflected the values of their local communities. When those communities change their ideas about sexual activity, so too do their local schools. Educational change hasn’t come from high-level meetings by New York leftists, but rather from more nebulous and hard-to-trace shifts in social trends.

Why do more and more young people seem to be avoiding early sexual activity? I don’t know, but I’ll guess: It’s not due to any sex-ed curriculum they’re receiving in their Health classes. No, the change in reported sexual activity is more likely due to changes in our whole society about the allure of sexual intercourse. After all, as we like to say here at ILYBYGTH, schools don’t change society, schools ARE society.